In the frost-bitten periphery of late 19th-century Russia, where the spires of Orthodox monasteries pierce a leaden sky, lives a young nun named Indika. She is unremarkable in every way—except for the fact that she shares her headspace with a silver-tongued incarnation of the Devil.

This is the unsettling premise of INDIKA, a third-person cinematic adventure released on May 2, 2024. Developed by Odd Meter, an independent studio that fled Moscow for Kazakhstan following the invasion of Ukraine, the game is less a traditional entertainment product and more a blistering, surrealist interrogation of religious dogma, moral philosophy, and the crushing weight of institutional authority.

The Exodus of Odd Meter

To understand INDIKA, one must first understand the state of its creators. Led by game director Dmitry Svetlow, the team at Odd Meter found themselves at a crossroads when the geopolitical landscape shifted in 2022. The game’s development became an act of defiance, with the studio eventually receiving public backing from figures like Dmitry Glukhovsky (the Metro 2033 author), who shared their anti-war sentiments.

In an interview with PC Gamer shortly before the game’s launch, Svetlow was candid about the studio’s stance and the influence of their cultural heritage. “Religion is a tool of control,” Svetlow remarked, speaking on the game’s core themes. “We wanted to explore how this tool works on a human level, especially in a country where the church and state are so closely entwined.” This real-world displacement colors the game’s atmosphere; there is a palpable sense of isolation and the “otherness” that permeates every frame of Indika’s journey.

A Mechanics of Cognitive Dissonance

INDIKA defies easy categorization.

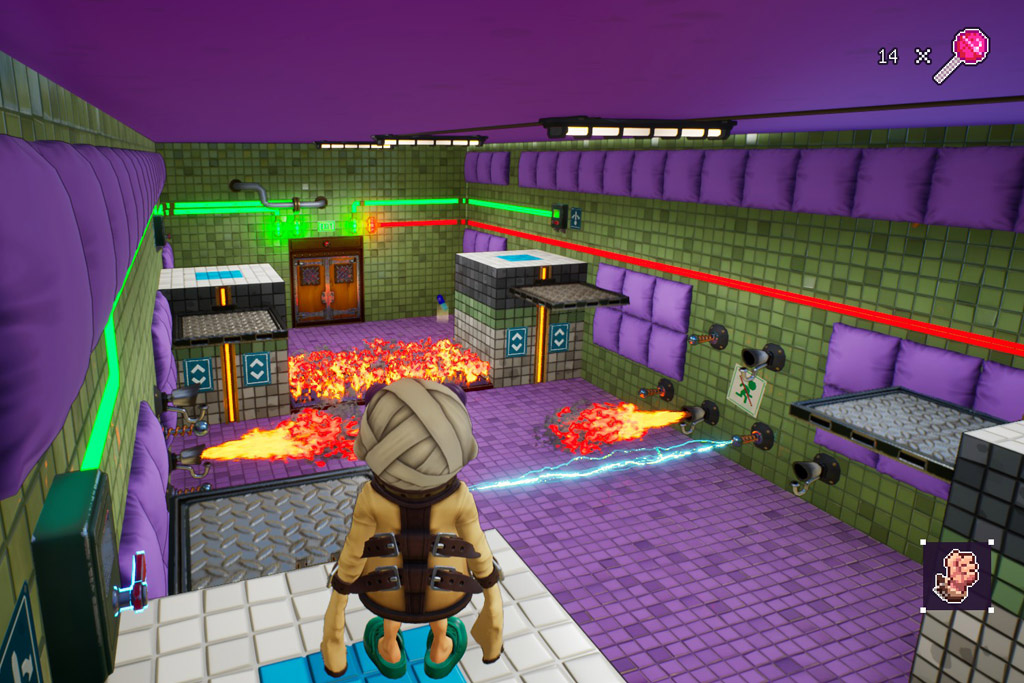

It is a “walking simulator” in the broadest sense, yet it constantly interrupts its own rhythm with jarring, avant-garde design choices. The gameplay is a blend of environmental puzzles, third-person exploration, and—most controversially—16-bit pixel art mini-games that serve as flashbacks to Indika’s life before the convent.

The most striking mechanical feature is the “Prayer System.” As Indika traverses the surreal landscape—where architecture often defies gravity and proportions shift like a fever dream—the Devil’s voice whispers blasphemies into her ear. The screen distorts into a hellish, fractured red landscape where paths are blocked or destroyed. The player must hold a button to pray; as Indika recites her psalms, the world reverts to its mundane, “real” state, allowing her to pass through the delusion.

It is a literal representation of faith as a coping mechanism—a way to ignore a fractured reality. However, in a move that feels pointedly cynical, the game rewards the player with “experience points” for finding religious icons and lighting candles, only to inform the player via a loading screen that these points are entirely useless. It is a biting critique of “gamified” spirituality.

The Philosophy of the Absurd

The narrative follows Indika as she is cast out of her monastery to deliver a letter. Along the way, she meets Ilya, a fugitive with a gangrenous arm who believes God is speaking to him through the rot. The interplay between Indika’s internal demon, her own burgeoning skepticism, and Ilya’s fanatical delusions creates a triadic philosophical debate that mirrors the works of Dostoevsky or Bulgakov.

Svetlow has cited the influence of Russian literature’s preoccupation with the “superfluous man” and the struggle for the soul. In a feature with Game Developer, Svetlow explained the intention behind the game’s discomfort: “We wanted to show that the path to true morality isn’t found in following a set of rules, but in the painful process of thinking for oneself. Indika is a character who has been told what to think her whole life. The Devil is simply the voice of her own logic, which she has been taught to fear.”

The game’s visual language reinforces this. The world is populated by impossibly large steam-powered machinery and gargantuan fish, reflecting a society caught between ancient mysticism and an industrial future it cannot quite comprehend. The architecture is oppressive, designed to make the individual feel infinitesimal.

The Visual Grammar of Indika

To understand the depth of Indika’s spiritual crisis, one must look past the dialogue and into the visual grammar of the world Odd Meter has constructed. The game is saturated with the iconography of the Russian Orthodox Church, yet it utilizes these sacred symbols to emphasize a profound sense of alienation rather than comfort.

The Icon as a Silent Witness

Throughout the journey, the player encounters “Red Corners”—traditional domestic shrines where icons are displayed. In Russian culture, the Krasny Ugol was historically the most important part of the home, a place where the divine intersected with the mundane. In INDIKA, however, these icons are often found in states of decay or jarring displacement.

The game’s puzzles frequently revolve around these religious artifacts. In one instance, Indika must manipulate heavy machinery to move a massive, gilded icon, turning a sacred object of veneration into a mere mechanical counterweight. This serves as a visual metaphor for the studio’s critique: the reduction of spiritual truth to institutional utility. The gold leaf and the stern, unblinking eyes of the saints do not offer Indika guidance; they act as silent, judgmental observers of her trauma. By interacting with these icons through the lens of physics puzzles, the player experiences the “weight” of tradition in a literal, burdensome sense.

The 16-Bit Escape: Nostalgia as Trauma

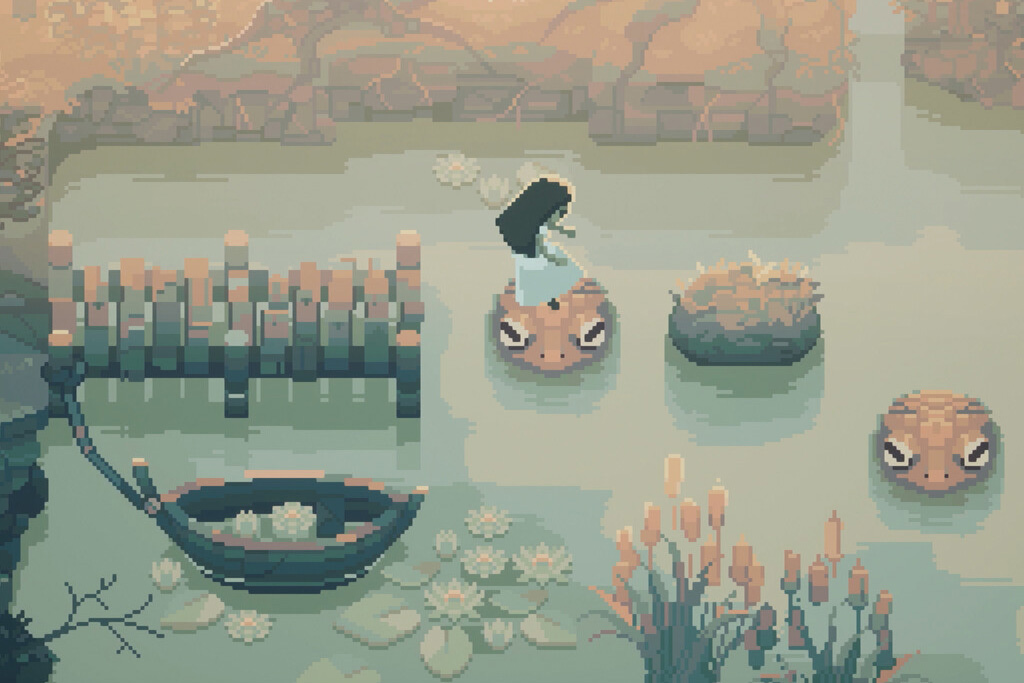

Contrasting the oppressive, photorealistic gloom of the Russian winter are the game’s 16-bit pixel art sequences. These segments, which play like frantic arcade games from the 1990s, serve as a brilliant narrative device to explore Indika’s childhood. By shifting the medium, Svetlow and his team create a “psychological buffer.” These sequences represent Indika’s memories before the convent—a time when her world was simpler, yet already being fractured by the expectations of others.

The use of high-energy, “primitive” gaming aesthetics to depict tragic backstories creates a jarring cognitive dissonance. It suggests that Indika’s memory has “compressed” these traumas into a manageable, game-like format to survive them. While the 3D world represents her current, suffocating reality, the 2D world represents the frantic, colorful, and ultimately doomed attempt to outrun her destiny. This stylistic whiplash reinforces the Devil’s argument: that the world is an absurd, chaotic place where the rules—whether of physics or of faith—are fundamentally rigged against the player.

A Dialogue of Styles

The interplay between the “Sacred” (the Orthodox icons) and the “Profane” (the 16-bit mini-games) creates a unique dialectic. While the icons represent a static, unchanging past that demands submission, the arcade sequences represent a dynamic, chaotic past that Indika is still trying to “beat.” Together, they illustrate a woman trapped between a history she cannot change and a faith she cannot feel, leaving the player to navigate the wreckage left in the middle.

To provide a comprehensive view of the theological architecture in INDIKA, it is essential to look at how specific religious objects are repurposed within the game’s mechanics. The developers at Odd Meter do not just use icons as “set dressing”; they use them as a language to describe Indika’s internal fracture.

The Iconography of Dissent: Sacred vs. Profane

The following table categorizes the primary religious symbols encountered in the game, comparing their traditional Orthodox significance with their narrative “subversion” within the world of INDIKA.

Designed to be Uncomfortable

In an industry that often prioritizes “player comfort” and “satisfying loops,” the discomfort in INDIKA is a deliberate, meticulously crafted feature. The developers at Odd Meter view this friction as the only honest way to explore their chosen subject matter.

During a deep-dive interview with PC Gamer, game director Dmitry Svetlow articulated the necessity of this unease. He explained that to truly critique the stifling nature of dogma, the player cannot be allowed to feel “at home” in the world.

“We didn’t want to make a game where you just walk around and feel good,” Svetlow stated. “The story is about a person who is constantly at war with herself and the world around her. If the player feels comfortable, then we have failed to show Indika’s reality. The discomfort is a reflection of her internal state—the feeling that everything is slightly ‘wrong’ or ‘too much.'”

In another conversation with Game Developer, Svetlow expanded on the intent behind the game’s stylistic shifts and nihilistic mechanics:

“Life is often absurd and uncomfortable. For Indika, religion has become a set of chains, and the Devil is the only one speaking sense, but even that sense is painful. We want the player to feel that pressure—to feel the weight of the architecture and the pointlessness of the rituals. It’s meant to provoke a reaction, not just to entertain.”

This commitment to discomfort is evident in the “Faith Points” system. As previously mentioned, the game provides the player with an immediate dopamine hit for collecting religious icons. This is immediately undercut it with a UI message stating the points are “pointless.” By subverting the most basic expectations of video game rewards, Svetlow forces the player into a state of existential frustration.

The goal is to move the player beyond the role of a consumer and into the role of a witness to Indika’s psychological unraveling. The discomfort isn’t just an aesthetic choice; it is the game’s central thesis.

A Rare Specimen

INDIKA is a rare specimen in the modern gaming landscape. It is a high-fidelity, polished experience that carries the soul of a scorched-earth indie manifesto. By stripping away the power fantasies typical of the medium, Odd Meter has created a mirror. As an investigative piece of software, INDIKA reveals the cracks in the foundations of organized belief systems. It asks whether a person can truly be “good” if their goodness is compelled by fear, and whether the voice we call “evil” is sometimes just the sound of a mind waking up.